The safety of graphene in human health:

what science says about it

Part II. Are graphene materials safe for humans?

The family of graphene materials comprises a wide range of two-dimensional (2D) carbon nanostructures in the form of sheets that differ from each other by the particularities derived from the production method or by the innumerable functionalizations that can be performed after its obtaining. In 2022, Nature magazine, one of the most important scientific journals in the world, published a study in which 36 products from graphene suppliers from countries such as the United States, Norway, Italy, Canada, India, China, Malaysia and England were analyzed, concluding that graphenes represent a heterogeneous class of materials with variable characteristics and properties, whether mechanical, thermal, electrical, optical, biological, etc., which can be transferred to a large number of three-dimensional (3D) compounds to modify or create new products.

“Undoubtedly, graphene and nanotechnology in general continue to be controversial issues as they confront us with a world that is difficult to see and understand, but with simply amazing effects”

Are graphene materials safe?

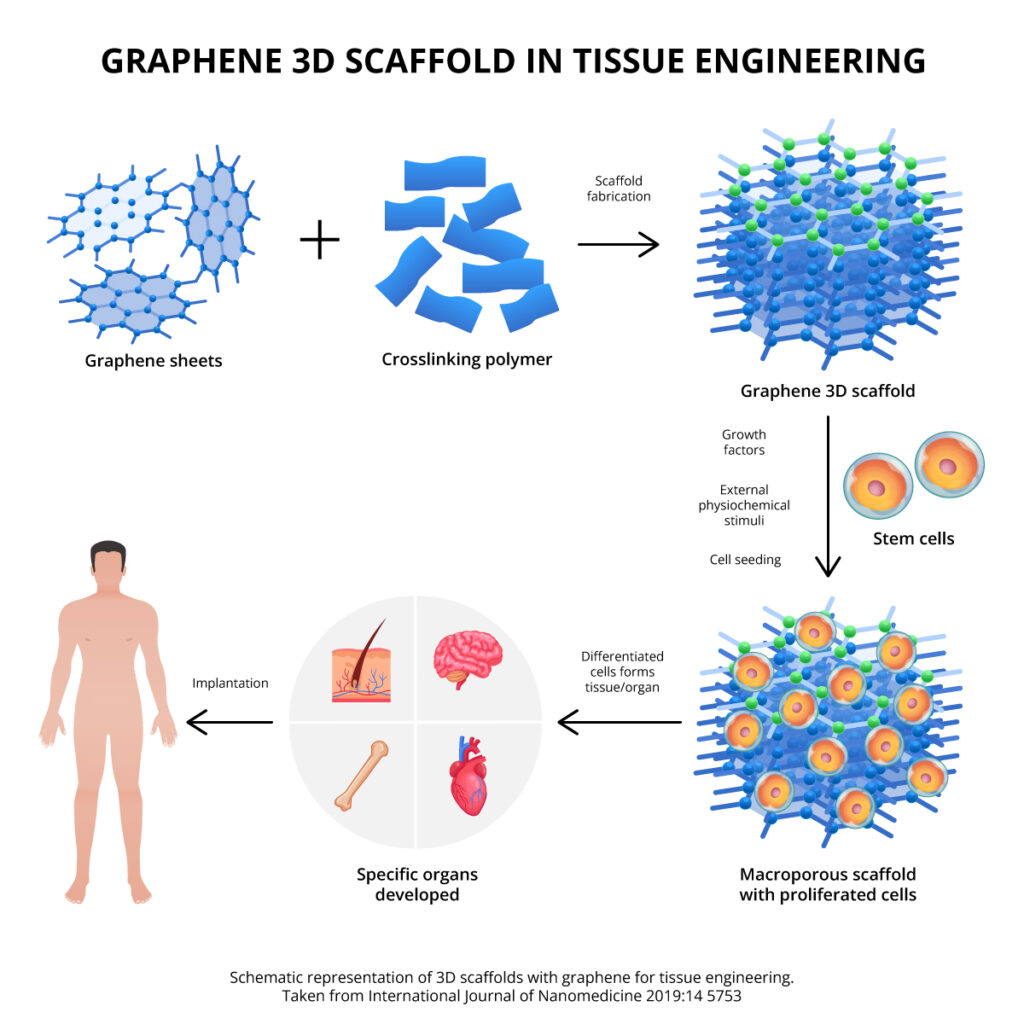

Graphene materials promise to be an important tool within biomedical technologies. In principle, its benefits can be used for the design of diagnostic elements such as sensors and devices for images up to neural interfaces, gene therapy, drug delivery, tissue engineering, infection control, phototherapy for cancer treatment, bioelectronic and dental medicine, among other. But for them to be truly used in this type of technology, their interactions with the biological environment must first be understood or, failing that, ensure that their presence does not alter the natural environment of the cells. In this sense, numerous studies have been carried out with the different forms, presentations, and available concentrations of graphene whose findings have gradually paved the way for its safe use in biomedical technologies:

i) Graphene materials in their free form. In in vitro tests, exposure of human lung epithelial cells to graphene sheets at concentrations lower than 0.005 mg/ml did not cause significant changes in their morphology or adhesion,2,3 nor was cytotoxic activity identified in stem cells derived from adipose tissue. human, periodontal ligament and dental pulp exposed to 0.5 mg/ml of GO,4 even and understanding a possible dose-size dependent effect, other investigations report safe concentrations below 40 mg/ml or, that do not exceed 1, 5% w/v. 5-8

Finally, one of the most recent in vivo studies published by the University of Manchester, United Kingdom, on the pulmonary response of mice exposed to graphene oxide (GO) in the respiratory tract, did not identify significant damage or pulmonary fibrosis at 90-day follow-up. These results provide solid grounds for the safety of these nanostructures without underestimating basic safety measures, such as avoiding their inhalation.9 Likewise, scientists from the University of Trieste, Italy, analyzed the impact of graphene materials on the skin, reporting low toxicity on cells.10

“It is unlikely that graphene materials in their free form are used to be in contact with the biological environment, they are generally functionalized or immobilized in other materials to develop an application”

ii) Functionalized graphene materials. Functionalization is the term that refers to the chemical modification of a nanomaterial to give it a “function”, that is, to facilitate its incorporation with other compounds or to benefit its biocompatibility and better direct its use by anchoring functional groups, molecules, or nanoparticles. A study published in the journal Nature Communications on graphene bioapplications highlights the importance of its functionalization with amino groups to make it more compatible with human immune cells.11,12

“The most common functionalization of graphene is the anchoring of oxygenated groups on its surface, this material is known as graphene oxide”

iii) Immobilization in polymers. The use of graphene materials as nano-filling for plastics, resins, coatings, etc., is the most common way in which these nanostructures are used. For the biomedical sector, its immobilization in polymers has shown good biocompatibility and stimulation of cell proliferation; antimicrobial activity and improvement of the mechanical properties of polymers, being classified as excellent candidates for the manufacture of bone fixation devices, molecular scaffolds, orthopedic implants, or dental materials.13-15

Given the great potential of graphene materials in health sciences, but also due to the many questions about their safety, an international research team from the European Graphene Flagship project, led by EMPA (German acronym for the Federal Institute for Testing and Materials Research), conducted a study to assess the potential health effects of graphene materials immobilized within a polymer; the results showed that the graphene particles released from said polymeric compounds after abrasion induce insignificant effects.16

“It is reassuring to see that this study shows negligible effects, confirming the viability of graphene for mass applications. Andrea C. Ferrari, Graphene Flagship Science and Technology Officer.” 17,18

Energeia-Graphenemex, the pioneering Mexican company in Latin America in the research and development of applications with graphene materials, throughout its 10-year career has overcome numerous scientific and industrial challenges to reach the market with products for industrial use. In 2018, it began to explore the antimicrobial capabilities of its products with excellent results in vitro and in a relevant environment; currently, and in conjunction with other research centers, it is carrying out evaluations to explore the potential of its materials as nano-reinforcement of biopolymers.

Drafting: EF/DHS

References

- Cytotoxicity survey of commercial graphene materials from worldwide. npj 2D Materials and Applications (2022) 6:65

- Biocompatibility of Pristine Graphene Monolayers, Nanosheets and Thin Films. 2014, 1406.2497.

- Preliminary In Vitro Cytotoxicity, Mutagenicity and Antitumoral Activity Evaluation of Graphene Flake and Aqueous Graphene Paste. Life 2022, 12, 242

- Biological and physico-mechanical properties of poly (methyl methacrylate) enriched with graphene oxide as a potential biomaterial. J Oral Res 2021; 10(2):1

- Graphene substrates promote adherence of human osteoblasts and mesenchymal stromal cells. Carbon. 2010; 48: 4323–9

- Multi-layer Graphene oxide in human keratinocytes: time-dependent cytotoxicity. Prolifer Gene Express Coat 2021; 11:1

- Cytotoxicity assessment of graphene-based nanomaterials on human dental follicle stem cells. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2015; 136:791

- Arabinoxylan/graphene-oxide/nHAp-NPs/PVA bionano composite scaffolds for fractured bone healing. 2021. J. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 15, 322.

- Size-Dependent Pulmonary Impact of Thin Graphene Oxide Sheets in Mice: Toward Safe-by-Design. Adv. Sci. 2020, 7, 1903200

- Differential cytotoxic effects of graphene and graphene oxide on skin keratinocytes. 2017. Sci Rep 7, 40572

- Amine-Modified Graphene: Thrombo-Protective Safer Alternative to Graphene Oxide for Biomedical Applications. ACS Nano 2012, 6, 2731

- Single-cell mass cytometry and transcriptome profiling reveal the impact of graphene on human immune cells. Nature Communications, 2017, 8: 1109,

- In-vitro cytotoxicity of zinc oxide, graphene oxide, and calcium carbonate nano particulates reinforced high-density polyethylene composite. J. Mater Res. Technol. 2022. 18: 921

- Graphene-Doped Polymethyl Methacrylate (PMMA) as a New Restorative Material in Implant-Prosthetics: In Vitro Analysis of Resistance to Mechanical FatigueJ. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 1269

- High performance of polysulfone/ Graphene oxide- silver nanocomposites with excellent antibacterial capability for medical applications. Matter today commun. 2021. 27

- Hazard assessment of abraded thermoplastic composites reinforced with reduced graphene oxide. J. Hazard Mater. 2022. 435. 129053

- https://www.empa.ch/web/s604/graphene-dust

- https://www.graphene-info.com/researchers-asses-health-hazards-graphene-enhanced-composites